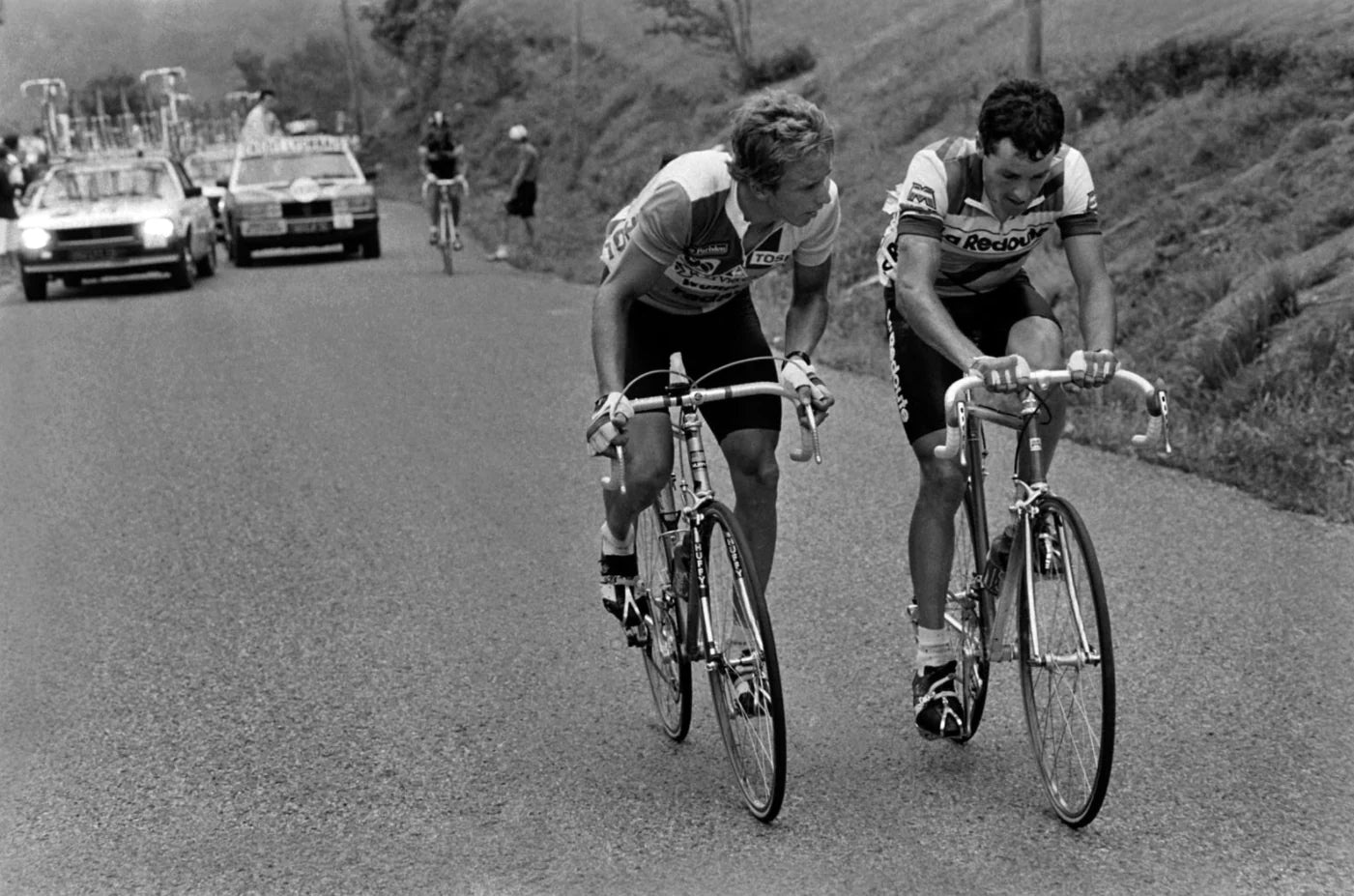

For my husband, born in France, there are only two sports: soccer, which he played semi-professionally before moving to the U.S., and cycling. Soccer plays year-round on our TV, and I’ve come to know teams, players, even coaches, as well as terms for play—off-side, corner, penalty, shoot-out—watching the players dribble up and down the field, ball between their feet. But come July, our TV is tuned to the twenty-one stages (race days) of the three-week cycling marathon, the Tour de France. Here are players and teams, too, but the players are virtually unrecognizable, helmeted in their casques, and I have a hard time figuring out how exactly the teams in their same-colored shirts are playing together, scattered throughout the vast peloton, the horde of cyclists making their way along hundreds of miles like ants on the march. There’s the occasional échappée (escape) of the leaders from the pack, but literally nothing much else to watch—heads bobbing up and down, bikes tilting side to side. All I can focus on, beyond gorgeous views of French countryside, is how each cyclist manages to keep up that same repetitive motion of peddling mile after mile, how he endures the climb, day after day, up all those extreme French mountains at grades of as much as seven or eight percent. I try to imagine the suffering.

Now, in "The Cyclist and His Shadow", translated from the French by François Thomazeau, Olivier Haralambon tells us exactly what it is to be that cyclist, his suffering—and his euphoria. Haralambon’s book is something quite different from an experiential description you might find in an adventurer’s magazine. It is, rather, a poetic treatise on the existential reality of the cyclist, its prose a mesmerizing pastiche of virtuosic descriptive language and metaphor, as if the author wants not merely for us to understand what it is to pedal in the cyclist’s shoes, but how it renders the cyclist something other than himself—in body, mind, and soul. Linguistically, Haralambon captivates even the never-professional-cyclists among us. As someone who has long loved and studied French, I hear the flavor of the original in what the translator calls the “slipstream” of Haralambon’s language, vividly wrought to inspire our imagination and pleasure.

“Who never fell asleep in front of a Tour de France stage?” Haralambon begins, rhetorically, knowing that for many of us, “cycling races are a dreadfully monotonous spectacle.” He writes,

You might notice, that the pace of [the cyclists’] legs varies, that they accelerate sharply from time to time, that they stand up on the pedals and then sit back in the saddle; you might, should you know the toughness of some climbs at a given place, roll your eyes at the speed at which they tackle them, but…after a puzzled bout of disbelief, halfway between respect and pity for the sight of their suffering faces, you look away and turn to something else.

But cycling was something Haralambon could never turn away from, after the moment he first rode, at the age of thirteen, on a country road, and “found myself in the space opened inside me by the landscape separating my eyes from my muscles…and my soul was ripped open like a fruit whose overripe flesh was a promise of infinity.”

In passage after passage, I hear echoes of the long tradition of French philosophic musing, as Haralambon exposes for the reader the ineffable that he has experienced through cycling:

I loved pedaling breathlessly beside the demon of my shadow. I pulled it behind me mercilessly for tens of thousands of kilometers and it never ever let me down. I sweated, cried, spat, came, dribbled, bled sometimes on the tarmac and the landscape. I have loved the bike and I have loved racing fiercely because they gave me a form of trust in the unfathomable immensity of life, in the verticality of time. Without it, without them, I would never have had the slightest feeling of eternity—not as a myth but as an experience.

Far from being the perpetrators in a “monotonous spectacle,” “the best competitive riders,” he argues, “are among the cleverest and the most subtle individuals in the human race…as delicate as ballet dancers and more astute than many writers.” As if to prove just that point, Haralambon exhibits his skill as a writer on page after page, as in this passage about coming of age as a young competitive rider:

We felt like rising stars…all the neighborhood girls were at their windows, chatting and calling each other. The façade of the building looked like an Advent calendar. Behind them, you could feel the polished kitchens, the put-away dishes and the pink rubber gloves thrown over the faucets like the remains of Michelangelo in the arms of St. Bartholomew on the walls of the Sistine Chapel.

Though Haralambon gives the insider’s privileged view of all the facets of competitive cycling—the training, the solitude of the individual, the “monstrous” nature of the rampaging peloton, even the doping—it’s his encounter with the existential that drives the narrative. Reading this book, I forgot what I had witnessed, obliviously, every summer on TV. I began to feel myself inside the soul of a person dedicated to two excruciating and unaccountably rewarding activities, cycling and writing, and to see the parallels between Haralambon’s experience as a cyclist and all the endeavours artists undertake that lead to transcendence:

He pushes on the pedals, rotates them, makes them dance, and moves ahead in the direction designed by the road lined by spectators…Yet the landscape that is the background of the show is not the real place of his meticulous effort. He performs and creates from the resonances of his solitude and carves in himself his own share of space.…He works with all muscles on the rough, indistinct, and endlessly improvable material of his most intimate life.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.